|

Having completed my third novel Stolen about a forbidden friendship between a Quaker girl and a Peramangk girl, I was almost ready to move on to another book with an entirely different focus. But

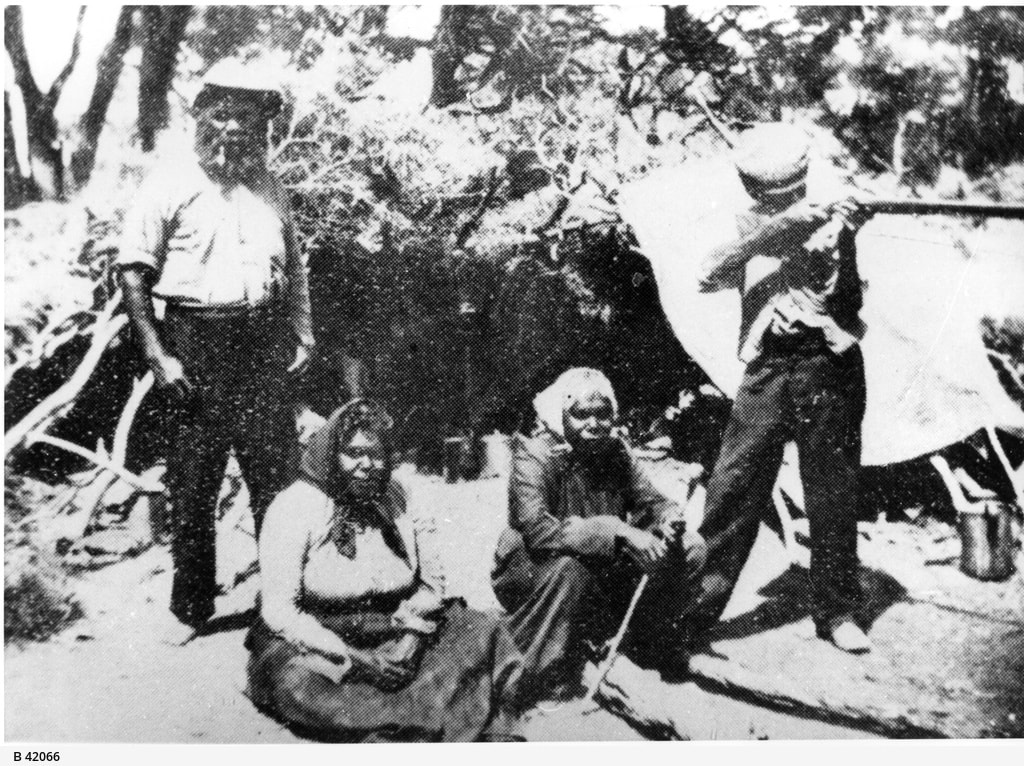

I’ve recently realised that writing Stolen is just the beginning of my journey towards truth telling. Stolen is written from a standpoint of curiosity. How did settler colonisers in South Australia allow and account for the near total destruction of Australia's First Nations people? Writing it has been a sharp reminder that my very existence and the privilege I have - resources, education, free time, health, social contacts - are built upon the destruction and devastation of the first people of this country. I wrote it knowing that my ancestors could not have been entirely oblivious about what was happening around them. There are no family stories of any of them speaking up so at best they may have passive bystanders, unprepared or maybe in some cases, unable, to speak against what they saw. I chose Echunga as the primary setting for Stolen for two reasons. My mother’s ancestors, through her father, settled and colonised there in 1838, two years into South Australia’s European history. I was also drawn to the fact that many of the early colonisers there were Quakers (my ancestors were not as far as I have been able to determine), a group who had been very active in the abolition of slavery in other parts of the colonised world. I was also drawn to the fact that there had been a mini gold rush in Echunga in the 1850’s, the very time I wanted to set my novel in. I began writing with the idea that I would avoid any risk of cultural offence by backgrounding the Aboriginal presence. By not focusing on the fact that Aboriginal people were there, I could, I thought, avoid causing offence. This stage lasted barely a couple of weeks before I realised I could not, would not, intentionally add to the plethora of literature that whitewashes First Nation people from our known history. I would instead, I decided, simply be vigilant to make sure the novel was written entirely from a sympathetic European point of view and voice; the voice of a child with speech disability, a disability that allowed her to see the world differently from her family and peers. This would surely avoid the risk of causing offence, I thought. But from the moment I included a significant plot role in Stolen, for an Aboriginal character, Kiani, a strong and resilient young Peramangk woman, I knew I had to do everything I could to engage with a cultural consultant. I contacted the reconciliation group located on Peramangk country and was referred to a Peramangk man who was immediately responsive to my request and expressed support for what I was doing. After several in-depth emails he offered to read an early draft and also, to my delight shared with me his recently completed Master’s dissertation about his own life as a stolen child and the complexities of Aboriginal identity. I was one of the first readers outside of his academic support group, a privilege that I continue to cherish. I learned so much from it about the ongoing impact of the laws set up during early colonial times. Career changes impacted on his ability to read all of the novel but he was very positive about what he was able to complete. He was keen that I contact his sister who he said was better equipped to give me feedback as she herself was a creative writer. She in turn was very generous and encouraging but was managing a raft of projects. She referred me to her daughter, a student of Law and also of Creative Writing. She was very excited to hear what I was writing about and expressed her support for my efforts to have a Peramangk person read the novel. After a several emails and a covid epidemic I contracted her to read the novel and she provided me with assurance that there was nothing offensive in what I had written. Cultural consultation completed. I sent the manuscripts to publishers to await their response. So why was I left with the irksome feeling that I still had work to do; That my accountability to the first people of the country I was writing on was unfinished business? Weeks after submitting I attended the Historical Novel Society Conference and I began to understand even more deeply the complexities and problems for a non-Indigenous person such as myself, a second nation person, when writing Indigenous characters into creative fiction. I listened to an East coast salt-water First Nation woman (a multi-disciplinary lawyer, filmmaker, artist and scholar) asking ‘can we actually find a decolonised space with a nonindigenous ally?’. Then a writer and author living on Kaurna Yarta, winner of the 2020 Dorothy Hewett Award and the CBCA Honour Book, challenged me to think about the whiteness in publishing and reading world. She pointed out that non-indigenous people must trust indigenous people to do their own work. An award-winning novelist and playwright of Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Te Arawa, Ngāti Whakaue, Tuhourangi, Ngāti Tumatawera, Tainui and Pākehā descent asked ‘what are you bringing to this (cultural consultation) relationship?’. She reminded me to not expect all the work to be done by First Nation people. So, where was I in this debate? Unlike some of my fellow conference delegates, I was not upset that we were not given definitive answers by these First Nation women. I understood that they were not there to make us feel comfortable. But I too was left feeling directionless. My unfinished business remained. By pure chance I met, at the airport, a First Nations woman I’d come to know through my local Reconciliation Group. After yarning over a coffee about a whole range of things I put my dilemma to her. Her response initially puzzled me. “Where are you in the story?” I tried to explain that, as a writer of fiction, I was outside the story but that my beliefs and values were imbedded in the narrative. I explained how I’d exposed the role of the church and the government through the thoughts and judgement of my main character a white girl who herself was an outsider. I told her of how I’d used direct quotes from the Anglican bishop exposing his racism and critiqued the way the main character’s family had gone against their own pacifist teaching when it came to the First Nation Australian people’s whose land they were living on and took as their own. But still her question remained. ‘Where are you in the story? What was your family’s role? For example did they use the free labour of Aboriginal women as domestics?’ I found myself grappling for facts about my family: ‘they were mostly poor’, ‘one family owned a shop and they did have helper, but she was Irish I think.’ As I spoke, I remembered seeing a photo (see below) taken in 1925 of an Aboriginal family – probably Narungga – sitting by a salt lake at the edge of the town where I grew up and where my great grandparents had owned the general store from 1911 until 1933, the only source of non-native food and clothing for the region. And given that by 1925 most of the countryside had been cleared of trees to make way for broad acre cropping and sheep, it was very unlikely that the Narungga people had access to their food, clothing, shelter and cultural resources. How did they survive? It occurred to me that it was strange that in all the many verbal and written stories (including diaries, letters, autobiographies), passed down by that side of my family, not one mention Aboriginal people living nearby. ‘I assume they (the Narungga family) relied on my g-grandparents shop for food,” I said to my patient airport listener. She smiled and replied. ‘But they probably would not have been allowed into the shop Jen.’ A gaping hole of accountability opened up before me. I’ve known for many years that my privilege comes from being a descendant of white colonisers. But now I was being challenged to do the hard work of truth telling from within my own family a much more confronting task than being an objective story teller. So what will I change in Stolen? I will amplify my main character’s dissonance and have her giving into to the temptation to take the easy road by ignoring her Aboriginal friend. I will also change the ending slightly to, hopefully, more clearly engage my reader to consider the psychological cost of not engaging in personal truth telling and the even greater psychological cost of whitewashing our entire history. And for me personally? Well my business surely remains, unfinished. The attached image shows Aboriginal people who may have died, which may cause sadness and distress to their relatives. Care and discretion should be used when viewing the image. If you believe this image should be restricted from general viewing for cultural reasons please contact the Library's enquiry service 08 8207 7250 or [email protected]. The attached image shows Aboriginal people who may have died, which may cause sadness and distress to their relatives. Care and discretion should be used when viewing the image. If you believe this image should be restricted from general viewing for cultural reasons please contact the Library's enquiry service 08 8207 7250 or [email protected].

0 Comments

|

AuthorJennifer is a writer of short stories, novels and a family history. Archives

November 2023

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed